So, one thing about me as a musician is that I’m a guitarist who is deeply ambivalent about guitar solos in a rock or pop context. I’ll take a solo, sure, if it makes sense in the context of the song. But a lot of songs don’t need one.

Look, my problem with solos isn’t that they are solos. Some of the most transcendent pieces of music I have heard, and will ever hear, are extended improvisations. My problem, if you could call it that, is with players who are more focused on demonstrating their chops than they are on connecting with the audience. This tendency goes all the way back to that teenage or preteen point at which so many musicians start feeling the itch to learn an instrument. A lot of kids start playing an instrument for the same reason kids do a lot of things: to become very skilled at something, and subsequently show off how skilled you are. Which is cool, in that the beginner’s drive, and the rush of learning a skill, can really help push you down the road toward mastery. Some musicians eventually stop caring so much whether everyone notices them shredding, and some don’t.

I started to realize this dynamic at a pretty early age, fortunately sparing me the messy trial and error I probably would have undergone otherwise. The best lesson in soloing I’ve ever learned is one I learned when I was 16.

My first real instrument was the trumpet, and when I was in high school, I was in the jazz band. One thing you have to understand is that at the age when most band kids joined the jazz band, in ninth or tenth grade, they didn’t really know anything about jazz. They would come to learn a bit about how to play it, and how to listen to it. But at the outset, kids typically joined the jazz band because they wanted to show off. The degree to which you could show off was generally determined by what was written in the charts, as improvisation itself wasn’t really part of the curriculum. Solos were already written out note by note, and the charts were immutable. Every first chair trumpet player played the same solo on “In the Mood,” every single year.

We had one song in the books, though, that had an open-ended section for soloing. It was a straightforward 12-bar, so we could make room for however many solos the band teacher saw fit, without messing with the basic arrangement. I was given a chorus to solo over – but there wasn’t a trumpet solo in the chart. Not being much of an improviser at that point, I decided to just through-compose something and stash the notation in my music folder.

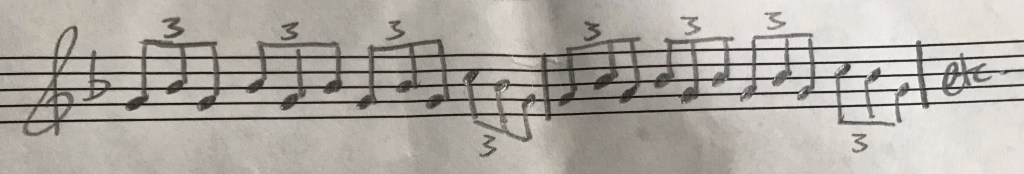

I decided I was going to write not exactly a blues solo, but a parody of a blues solo, because that was what passed for a joke with me at the time, I guess. We jazz band kids were in the habit of cutting each other up during rehearsals, anyway, venturing off-book and doing things like playing many or as few notes as possible. So I came up with a solo that started with something utterly stupid, played with great conviction, and gradually becoming more competent up until a big flourish at the end.

And to to get to “utterly stupid,” I started with two measures of triplets that used a total of only three individual notes, but mostly using only two. You might compare it, in a fashion, to the first guitar solo in The Beatles’ “Yer Blues” (2:27-2:50 in this vid – which is John, and is John’s sense of humor). Here’s what the lick that I played looks like on an actual chart:

The first public performance of this rendition of this song was a requisite biannual assembly, where all the kids in the school were mandated to sit in the auditorium and listen to nine or 10 different student musical ensembles perform, whether they liked it or not. Much tougher crowd than the evening concerts for the parents, but I wasn’t out to impress an audience of kids who either didn’t give me the time of day or habitually acted like a-holes to me for no good reason.

So when my chorus came up in the set, I stood up and started playing the easiest and most ridiculous lick I’d ever played that was audible from the audience. And after the first few opening notes, I heard some spare clapping out in the crowd. A few more notes and the sound became a wave of applause. The third measure brought on an auditorium-wide “WOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO!” All very surprising to me, as I thought: I’m not even doing anything up here.

Walking out of the backstage area and into the hallway felt a lot like A Hard Day’s Night, if the throng of screaming fans had about 20 people in it and they weren’t really running or trying to touch the musicians and also were speaking intelligibly. I thought it was hilarious. The thing I had intended as a parody registered with the audience as the real version of what I was parodying. Not as though I was about to say so. Instead I said something like, “Oh, wow, thanks!,” and thought, “My god, it’s easier than I thought to impress people.”

I’ve remembered this over the [unintelligible coughing and mumbling] years since that concert. Previously, I had thought that for a solo to go over well, it had to be a dazzling display of technical wizardly requiring top-tier chops and an athlete’s dedication to practicing. Turned out it really just took a passage that sounded “fun” and gutsy, with something like an audible beginning, middle, and end. I realized:

- Most people can’t tell what’s hard or easy to play.

- People like when a big, bold lick repeats.

- People like musical clichés, whether they know it or not.*

- People like melody, even in solos. People like when their heads can stay in the song, rather than being taken out of it.

These lessons came back to me the following year, during the football season. Our band teacher decided to switch around the selections the marching band played in the football stands between plays on the field. One switch-up was to take the highly truncated version of The Troggs’ song “Wild Thing” in our “stadium riffs” booklet, and to build out a new arrangement that more closely resembled the structure of the classic single. Three things to consider about “Wild Thing:” One, part of The Troggs’ ethos was a self-aware knuckle-dragging element. I mean, Troggs is short for Troglodytes. They were going for something here. Two, there’s an ocarina solo in the middle of the song that sounds like it’s played by someone who had never played an ocarina before. Three, people freaking love “Wild Thing.” I ended up taking the solo on the trumpet, since ocarinas aren’t loud enough to take a solo with a marching band. Again, I was able to fill in that solo section with whatever I wanted, so I decided to just, y’know – play it like the record. People like familiarity.

In reality, the solo on “Wild Thing” is barely more than a drone. There are like, five notes to it, and most of the solo sits on one. There’s a big, bold lick that repeats a few times, which I knew from prior experience people would eat up, without knowing you can play it on the trumpet by moving one finger up and down. Sure enough, in the stands, when I leaned into that solo, there was a collective “YEAH” (people like recognizing things they know!), and about two-thirds of the way in, the crowd, to drop another cliché, went wild.

Years of practicing and gigging with concert band, marching band, jazz band, chamber ensemble, and symphonic winds ensemble, immersing myself in the history of the music we were playing, so I could lay ‘em flat at 16 with a few bars I would’ve been able to play at 13.

But see, that’s the thing. That’s how playing, or anything else, works. People will practice and practice to master their instrument, and then once they’re able to play at a high level, some of them will be disappointed by how so many listeners want to hear something so simple. But, please, let’s think about this for a couple seconds. It feels and sounds simple to you, the expert player, because you’ve put the work in, and now you’re capable of playing at a level beyond what is required to connect with the audience. And that’s how it’s supposed to be. You put the work in so that you can get the right idea over easily.

The audience isn’t losing it for your relatively uncomplicated licks because they don’t understand music. They’re losing it for your relatively uncomplicated licks because those licks are hitting their ears in a pleasing fashion, and they appreciate that you’re doing something they don’t know how to do. If the audience is with you, you’re doing the right thing.

Three years later, I was home from college on semester break, and I went to my old high school band’s biannual concert. My brother, an alto sax player, was in his senior year. During the jazz band’s set, that old 12-bar number came up – and when one of the trumpet players stood up to blow a solo, they started playing the solo I wrote. Somehow, that little scrap of staff paper was still in the first chair trumpet folder, as if it belonged there and was a real part of the song. A freaking honor, if there ever were one.

* At one point in the late 2000s, I interviewed Tad Kubler, the lead guitarist of The Hold Steady, and this whole topic of musical clichés came up. We were talking about a certain progression that a great many rock musicians go through as they mature, which at least a couple members of The Hold Steady had also gone through. They had started out as kids mimicking the “big rock moves.” After they had gotten a bit older, they started to consider those licks corny, and they chose to move into slightly more esoteric musical territory, screwing with the pop formula and rock’n’roll conventions. “But eventually,” he said, “we just realized all of those big rock clichés are clichés because they’re awesome.”